Designing for Power Users: The Simplicity Trap

Applications used to be messy. Not so much today—and maybe we're worse off.

If you used apps in the 90s or 00s, you remember. Menus stacked on menus. Dialog boxes full of checkboxes you didn't understand.

MS Office is a perfect example. Word, Excel, Powerpoint. Every function you could imagine was there, buried under layers of menus and cryptic icons.

Users would often get lost. But for the most part, you could do whatever it is you set out do with with just a suspicion that it was possible.

Then the pendulum swung. Apple taught the industry to worship simplicity. Clean screens, fewer buttons, "it just works".

It looks and feels great. However, this often comes at the expense of critical information and controls, leading to pre-defined workflows that can be limiting for power users.

Consider the modern smart home app. When a device is offline, it might simply say "Unavailable." Why? Is the battery dead? Is there a network issue? Is the hub unplugged? The user is left to guess, with no diagnostic information to guide them.

Look at a social media feed. An algorithm decides what you see. You get no controls, no insight, no knobs to turn. People are conditioned to these opaque systems.

This swing toward over-simplification leaves power users stranded. They're handed rigid tools they can't inspect, understand, or bend. This hurts in consumer apps and is worse in the enterprise world, where users often have no alternative.

The answer is not to swing the pendulum back the other way. There's a middle ground, unlocked by thinking in terms of primitives. A primitive is a core concept the system works with. Something real in the user's world—or something the software makes meaningful. Identify and expose these primitives. Let complexity arise from how users combine them.

Good tools do this:

- Figma: layers, components and constraints. The UI is clean, but the relationships are visible. That's where the power comes from.

- Notion or Obsidian: the block or note. Start with text and end up with systems.

- In

lnav, the primitive is the log line. It has properties, structure, and tools to filter, query, correlate.

These tools don't hide complexity. They give you powerful concepts for you to use in as simple or complex manner as you wish. They give you leverage.

Finding the right primitives is not (just) an exercise in user experience or interface design. It's a product problem. It starts at ideation.

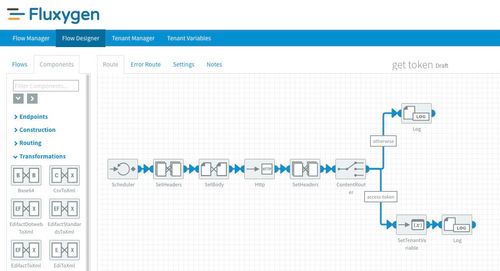

When I designed what became Fluxygen, I borrowed primitives from Apache Camel like exchanges and endpoints. Then I added new ones on top, such as flows and components.

Flows could be catalogued, versioned, validated, annotated, audited, templated.

Components could be grouped, composed, and extended.

Under the hood, Camel still ran. But users worked with flows and components. The model matched their intent. When they needed to reach down to the more granular primitives from Camel, they were still there, available for end-users to abuse (and abuse they did!).

When designing a system or application, your goal is to find the right primitives.

Iterate on them, expose them, build around them. Then let your users go wild.