Command-line Tools for Fast Log Forensics

In today's world of distributed systems, you'd think log aggregation and correlation tools would solve every mystery. In my experience that's often not the case. Most of these tools are heavy, sluggish, and overkill once you’ve narrowed the problem down to a single component. I find they slow me down.

In those situations I reach out to the same trusted command-line tools I've been using for many years. They are often all I need to sift through massive log files and extract the insights I'm looking for, with a much faster feedback loop than what I'd get from large observability suites.

In this post I'll go over some of those tools.

The classic Unix workhorses

Lightweight, fast and available everywhere. These likely won't be new to you.

grep + less are my go to for performing quick pattern searches.

With grep I prefer case insensitive searches (-i) and to include a few surrounding text lines for additional context (with -C, -B or -A).

$ grep --color=always -C 3 -i "nullpointer" application.log | lessI usually pipe the scrollable output to less (the powerful replacement for more!), for easier traversal of content.

Color highlighting of matches makes reading search results more comfortable.

less is also an incredible tool to use standalone, in interactive mode.

Its Emacs-like keybindings for line and screen navigation don't betray your muscle memory, and its expression matching, although basic when compared with grep, is often enough.

In follow mode, set by passing +F, it's similar to tail -f but with the added convenience of it being toggleable in-process (press Shift+F).

grepandlessare both designed for streaming content, handling multi-GB files with ease. However, certain operations in large enough files can start to feel sluggish. In those cases I recommend splitting the files before processing them.head,tailandsplithelp with this.

sort, uniq, cut and awk are what can be called signal amplifiers, particularly when used in a pipeline with grep.

sort in particular can be quite useful with logs, however keep in mind that it can be an expensive operation.

uniqonly removes consecutive duplicates, so you'll likely want to sort the lines beforehand

You can improve the situation by paralellizing, with --parallel, or better yet by narrowing down the portion of the lines to use for sorting.

$ grep -i "foobar" *.log | sort -t: -k2 --parallel 4In the example above we're searching for the keyword foobar across different log files.

Grep will prefix the matched lines with the file name and the colon character.

With -t we instruct sort to treat the line as fields delimited by colon, and then with -k2 we tell it to sort on the second field, so in the content after the prefix (while still retaining the prefix).

cut and awk are both used to extract fields/columns from lines of text, with the former having a streamlined but limited API, and the latter being much more powerful - even adequate for reasonably complex parsers.

Which one you reach for depends on the structure of your input and what you want to extract from it.

cut is adequate when the input has consistent delimiters and all you want to do is grab fixed-position fields.

For anything more than that, you'll need to reach out to awk.

My approach usually starts with grep, then I pipe its output through one or several signal amplifiers, then finally to less for consuming the results.

The new(er) kids on the block

While the old & faithful having been helping developers and sysadmins for decades, some other tools have gained popularity in more recent times, and earned a place in my toolbelt.

JSON is everywhere and is often downright abused in massive payloads.

jq enables structured filtering and searching through JSON content.

While grep gives you line-based matching, jq lets you inspect structured content in JSON, field by field.

$ jq 'select(.level == "ERROR")' payload.json

$ jq '.timestamp, .status' payload.jsonripgrep is a grep alternative (in many cases, a drop-in replacement) that attempts to be better suited for software development environments.

It does so in some subtle ways, such as respecting .gitignore exclusions, having more extensive support for regular expressions, and saner defaults for things such as recursive search, neatly formatted and colored output, and automatic skipping of binary files.

It also has better performance characteristics in terms of scaling with input volume, due to it being multi-threaded.

$ rg -i "nullpointer" -g "*.java"fzf is a fuzzy text finder that can be used for many different purposes.

It's often used together with your shell of choice to help perform reverse history search, or search through git branch names, for example.

I use it in place of less when I'm still hunting for a pattern and value flexible, fuzzy search over raw performance.

Do keep in mind that it holds the entire input in memory!

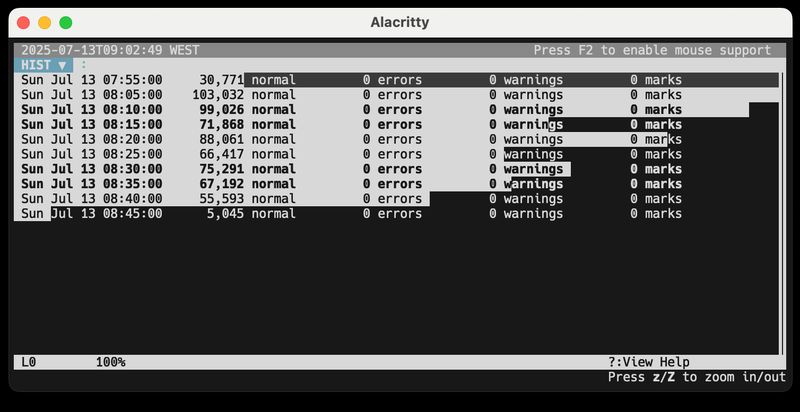

lnav is even moreso a tool that trades memory for convenience and interactivity.

While the other tools mentioned here follow the unix philosophy of having a narrow scope and being built for composability, lnav is a feature rich application meant to be used on its own, providing an advanced text UI (with mouse support).

It can be a time saver due to its auto-detection and support for common log formats, interactive search (similar to less) and filtering, automatic parsing of timestamps and ability to render entries in a histogram, and even an SQL based API - among many other features!

It is unlikely to be something you'll install at some remote machine, but for local debugging, given the proper log formats, it's hard to beat.

If you do need remote logs, mounting remote directories with something like sshfs might be more convenient than copying files.

When I'm in detective mode, the command line is my magnifying glass. Experiment with these and other tools — the time savings can be immense.